Keeping the Trust in Land Trust Work: Questions and Answers about Vermont S.119

by Jeanie McIntyre

Over the past several weeks there has been quite a bit of discussion about the permanence of conservation easement deeds in Vermont. Legislation (S.119) under consideration by the Vermont House Judiciary Committee would establish standards and a process by which most conservation easement deeds could be altered. VT Digger, an online news source, has published several op ed pieces by interested parties. Many readers responded.

Over the past several weeks there has been quite a bit of discussion about the permanence of conservation easement deeds in Vermont. Legislation (S.119) under consideration by the Vermont House Judiciary Committee would establish standards and a process by which most conservation easement deeds could be altered. VT Digger, an online news source, has published several op ed pieces by interested parties. Many readers responded.

Much of the commentary has focused on the intentions and expectations of landowners who conserve land. Do they believe that the easement will protect their land forever? What do land trusts tell landowners about how their conservation easement will be cared for over time? When the land trust and the landowner sign a conservation easement deed, who is bound to what?

These are important questions. For many landowners, the conservation easement is the single largest charitable gift they will ever make. Even landowners who are paid for their conservation easements give up significant opportunities for themselves and their heirs. Voluntary land conservation cannot happen without a great amount of landowner trust.

What is entrusted to the holder of a conservation easement? The phrase “permanent land conservation†contains ambiguity and some tension. “Permanent†cannot be “static,†because land is living and changing constantly. Landowners know this more intimately than anyone, and thus comes the challenge of writing conservation easement deeds that are strong enough to withstand momentary public sentiment and the personal and business convenience of future landowners while providing adaptive flexibility for the long-term changes that none of us can possibly anticipate.

UVLT has been following the issues and the progress of S.119 carefully. Here are our answers to some commonly asked questions.

Why is legislation needed?

At the moment, there is no single state statute that specifically addresses how and why conservation easements could be modified. Thus if a disagreement brings the parties to court, a judge will look to past precedential decisions of relevant courts. If a similar dispute has been resolved in the past, the court is usually bound to follow the reasoning used in the prior decision (this principle is known as stare decisis). The body of precedent is called “common law.” The Vermont Attorney General’s Office has indicated that there is scant precedent within the state for how common law would be applied to conservation easement deeds. Legislation would provide needed clarity and consistency.

What kinds of changes to conservation easements would be allowed under the new law?

S.119 would govern most conservation easement amendments. Within the bill, an amendment is defined as: “a modification of an existing conservation easement, the substitution of a new easement for an existing conservation easement, or the whole or partial termination of an existing conservation easement.†Examples of modifications were provided during testimony about the bill: the allowance of additional residences on a conserved parcel, the subdivision of a conserved parcel, the release of an easement on housing and buildings originally restricted by an easement, the termination of restrictions on one property in exchange for new restrictions placed on another property.

What rules are in effect today?

A patchwork of legal regimes presently apply to Vermont conservation easement deeds. One reason for this is that conservation easements arise from several different circumstances: some are purchased in conventional real estate transactions, others are conveyed as charitable gifts, including bequests, and yet others are compelled through governmental regulation or court-mandated settlement. Property law, contract law and charitable gift laws all may be relevant in any given situation.

A patchwork of legal regimes presently apply to Vermont conservation easement deeds. One reason for this is that conservation easements arise from several different circumstances: some are purchased in conventional real estate transactions, others are conveyed as charitable gifts, including bequests, and yet others are compelled through governmental regulation or court-mandated settlement. Property law, contract law and charitable gift laws all may be relevant in any given situation.

In addition, conservation easements are held by different types of entities: private charities, public agencies and municipalities. Each of these is subject to various rules pertaining to governance, asset stewardship and public accountability. For instance, charities must be truthful in soliciting contributions and must use contributions for the purposes for which they were given; towns generally cannot transfer real property interests without the vote of the governing body.

Finally, Congress has established preferential income tax treatment for donors of conservation easements, if the conservation easement gift meets federal income tax requirements. Those tax rules specify that the real property must be subject to perpetual restrictions. A growing number of federal tax court cases provide guidance for those involved with drafting and stewarding conservation easements for which federal charitable gift claims are made.

S.119 is over 40 pages long. Why is it so complicated?

S.119 seeks to bring all conservation easements within the scope of one law. Since there are so many different kinds of conservation easements and so many different entities that hold them, there are numerous processes described within this one proposed law. (There are more than two dozen bills under consideration by the Vermont House Judiciary Committee this session. Most are less than five pages long. S.119 is twice as long as the next longest bill.)

How will the rules change if S.119 is adopted?

S.119 would permit amendments, including replacements and terminations, if a panel of the Natural Resources Board finds that the amendment promotes or enhances the conservation purposes of the easement or enhances the public conservation interest. S.119 does not provide a definition for “conservation purposes of the easement.†Testimony and legislative discussion make plain that these are understood to be general in nature and not specific to the real property that was originally conserved. Conservation purposes or conservation intent could be enhanced, for instance, if the panel finds that conserving an alternative tract of land would better accomplish the purposes stated in the conservation easement. The panel may approve such an amendment even though it might not be consistent with the documented intent of the donor or other persons who funded the acquisition of the easement.

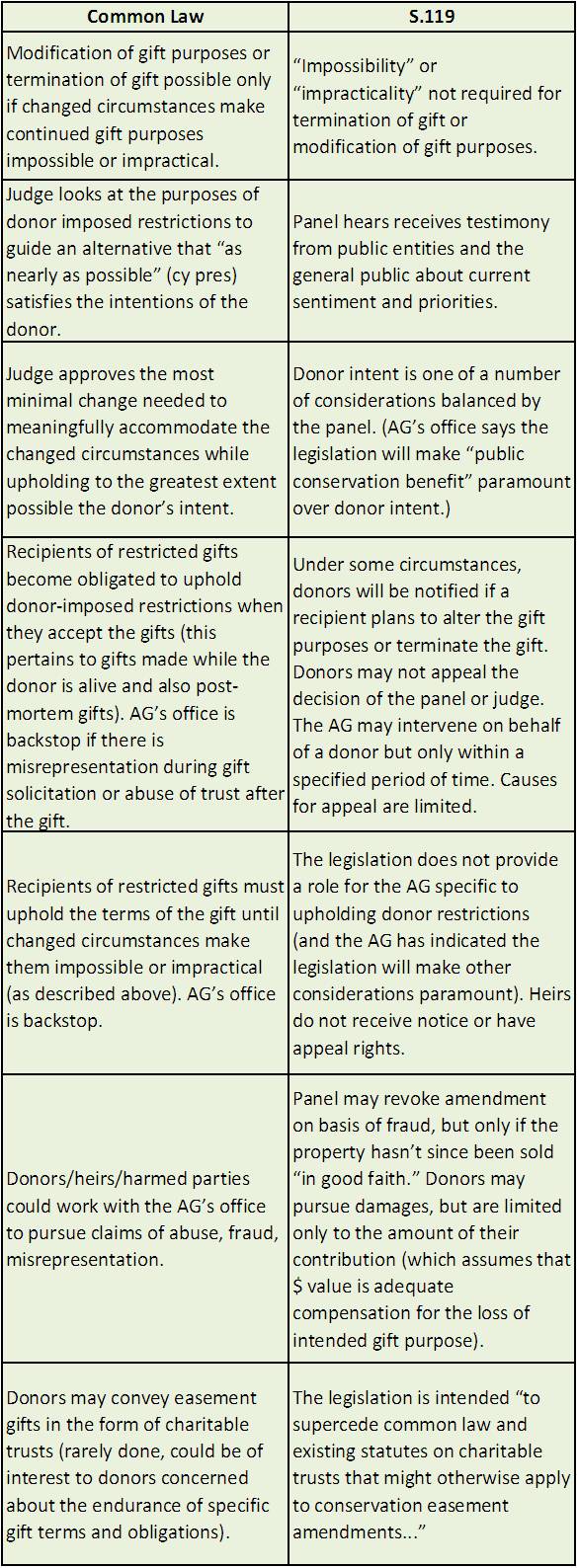

Common law pertaining to modification and termination of conservation “servitudes†is codified by the American Law Institute in Restatement (Third) of Property (Servitudes) Chapter 7, Section 7.11. Even though case law in Vermont is scant, these principles of law are clear. Although we can’t know with certainty how a case would be judged, we do know which legal precedents and guidance exist for a judge to rely on. S.119 is intended to fully replace and supplant any and all common law applicable to the amendment of conservation easements in Vermont.

Will S.119 change the federal rules for charitable gift treatment?

No. Regardless of what state laws are established, taxpayers and the entities which receive tax-deductible gifts will need to comply with the federal requirements.

Does S.119 increase public awareness and oversight of conservation easement amendments?

Yes. S.119 will create a broader process of third-party review. Common law provides for a judicial role for certain types of amendments, but does not require any public notice. Many land trusts in Vermont have amended conservation easements without consultation to the Attorney General’s Office, which has indicated that it has received no complaints, has limited staff resources and is not prepared to review land trust amendment proposals. S.119 will standardize application procedures and create a record of review. Also, neighbors, local officials, regional planners and the general public will be able to comment on the more significant conservation easement amendments.

Will the new law require land trusts to amend conservation easements?

No. The legislation specifies that an amendment may only occur if the holder(s) of the conservation easement and the landowner agree. A land trust could choose, at its option, to maintain internal policies that are more stringent than the requirements of state law.

Why has UVLT suggested changes to the current version of S.119?

We have heard from landowners, attorneys and financial advisors who would like assurance that land trusts and landowners will still be able to make agreements to protect specific parcels of land in perpetuity – and that these agreements will be backed by state law. These people recognize that the leadership and internal practices of land trusts may change over time. Though today’s land trusts may be trustworthy, state law should hold them accountable if they are not.

We agree with those who have pointed out that public involvement is not a substitute for honoring the expectations of donors – since many landowners choose conservation easements precisely because they do not have confidence in local planning and land use regulations.

We believe that it is possible to accomplish the goals of transparency, consistency and third party review without compromising the common law criteria and standards which are important to some donors. Our proposed changes would not impose these more stringent standards on land trusts and landowners who do not choose them. If S.119 is strengthened to provide greater protection for certain charitable gifts of conservation easements, the new law will successfully maintain the trust that has been so important to Vermont’s conservation achievements.

The Judiciary Committee has posted the bill and related testimony. (Scroll to find S.119, then click to locate uploaded documents.)